Friday, 29 March 2013

How Marketisation leads to Privatisation

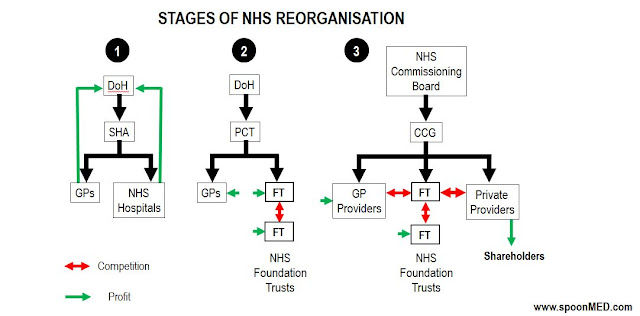

The 2012 Health and Social Care Act changes the NHS in ways which we are only just beginning to understand. These will have an impact on how healthcare is delivered and paid for in the future. Some have described it as a privatisation of the NHS by stealth. The changes to the NHS over the years are summarised here in three key stages.

1) Once upon a time: The Department of Health (DoH) funded all general practitioner (GP) and hospital services via Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs). Hospitals did not compete and healthcare was not motivated by profit. But the NHS was not efficient.

2) Creation of an Internal Market: The concept of relatively independent NHS Foundation Trusts (FT) was introduced in 2002. FTs were hospitals relatively free of DoH control and able to reinvest their own profits to improve local healthcare delivery. Local people could become FT members and have a say in how their local health services should be provided. Competition between FTs improved healthcare efficiency but would lead to the closure of less successful hospitals (and sadly some successful ones). Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) would commission (purchase) a variety of services from local hospitals.

3) 2012 Health and Social Care Act: Things are about to change. At the cost of £1.5 billion, PCTs have been disbanded and 211 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) created. These were supposed to be GP-led but in practice will be managed by support services outside the NHS. From April 1st 2013, CCGs will be responsible for a £65 billion NHS budget in England, commission (purchase) services from a wider variety of providers, and 'have flexibility to use competition as a means of improving NHS services'. Under Section 75 of the Act, CCGs/GPs will be forced to open up every part of the local health service to private companies via time-consuming tendering processes. These processes are almost alien to the NHS but familiar to private providers waiting in the wings. Private providers will compete with FTs. Some may collaborate with FTs but their ultimate objective will be to siphon off profits for shareholders.

PS. Since this blog was posted, the NHS Commissioning Board has been renamed NHS England.

Labels:

NHS

Saturday, 16 March 2013

The NHS: Connecting the Dots

Aneurin Bevan (1897-1960)

Since its creation in 1948, the National Health Service (NHS) has provided universal free healthcare in the UK via a comprehensive primary care programme (general practitioners), a network of secondary and tertiary care hospitals, a superb ambulance service and public healthcare programmes. The three core principles of the NHS at its inception were:

1. The NHS would be universal. Everyone would receive medical treatment when needed.

2. The NHS would be comprehensive. It would cover all aspects of healthcare from mental health to cancer, dentistry to cardiac surgery

3. The NHS would be ‘free at the point of delivery’. No patient would be ever be billed for their treatment, no matter how complex or frequent that treatment or care might be.

65 years later, the NHS is under some attack from sections of the media and government, not least because of the Francis Inquiry report which has highlighted failings in care at one NHS hospital. The culture of the NHS has been blamed. For most of us within the NHS, this brings into sharp focus the fact that staffing shortages, financial pressures imposed by government, increasing workloads and chasing of targets can lead to loss of morale and ultimately failure of healthcare. These are issues that can afflict all NHS trusts.

The Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt has described the NHS as 'mediocre' and 'coasting'. He has described the NHS as 'hitting targets but missing the point'. Roger Taylor has written much in support of the NHS but argued recently that ‘the Francis Inquiry report shows that those within the NHS cannot tell the difference between good healthcare and bad, and that we love the NHS too much to make it better (1)’. Enemies of the NHS will make the most of this opportunity to denigrate the NHS.

I argue here that despite its failings, the NHS is admired by many both in the UK and across the world (2). Those within and loyal to the NHS are in the strongest position to drive improvements in national healthcare delivery, continue to build on an NHS of which we have every right to be very proud, and take it into the future without compromising its core principles. At a time when the NHS is coming under much criticism, it is worth noting that in the US where a very different healthcare system operates, 62% of all personal bankruptcies are related to medical costs. Of these personal bankruptcies, 75% had previous medical insurance (3). Life expectancy in the UK has improved by 4.2 years between 1990 and 2010 (4). The UK had the largest fall in heart attack related death rates compared to any other European country between 1980 and 2006 (5). The US spends 2.4 times more on health per person than the UK, yet Britons live slightly longer than Americans. By laying the emphasis on universal and uniform healthcare delivery across the country, the NHS can and will connect all the dots in a way that many other healthcare systems cannot.

Labels:

NHS

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)